The Supreme Court recently heard arguments on a proposed bankruptcy settlement of legal claims concerning the opioid epidemic.

When it comes to companies putting the bottom line above the safety and lives of people, one of the earliest and clearest examples is the asbestos industry.

Asbestos companies also covered up extensive internal reports about the dangers of their product, afflicting millions of people with health problems, including many fatalities.

What’s going on in the Purdue Pharma lawsuit?

At center stage in the current SCOTUS case are members of the extended Sackler family, whose pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma developed OxyContin, a time-release version of the highly addictive opioid painkiller Oxycodone. Purdue’s OxyContin has been blamed by physicians and victims for playing a major role in the nationwide opioid health crisis.

An affiliate of Purdue Pharma already pleaded guilty in a criminal investigation by the Department of Justice, but at issue are the many civil lawsuits filed against members of the Sackler family who owned and ran the company. The lawsuits resulted in a massive settlement in which the Sackler defendants agreed to place $6 Billion in trust to compensate victims.

When companies behave wilfully or carelessly and hurt people, courts have routinely placed corporate money in trust to protect it for the people who were injured. But in this case, as part of the settlement, the Sackler family received immunity from future lawsuits, and there lies a controversy leading to the Supreme Court.

Both Asbestos and Opioid Manufacturers Were Hiding the Danger

The parallels between two seemingly disparate industries, asbestos and pharmaceuticals, come sharply into focus when examining the bankruptcy settlement of Purdue Pharma, owned by the Sackler family, in the wake of the OxyContin lawsuits.

Much like the asbestos companies of the past, Purdue Pharma faces accusations of willfully misleading the public about the dangers of its product, OxyContin. This article delves into the historical context of asbestos companies covering up the hazards of their products, drawing comparisons with the Sackler family’s bankruptcy settlement and the compensation trusts established for victims of both crises.

What Purdue and the Asbestos Industry Knew About the Dangers of their Products

What Purdue Knew

Purdue is accused of having extensive research about the addictive nature of its product, as well as the alarming rats it was being prescribed, often for ailments unrelated to its purpose.

For example, court filings indicate Purdue was informed that many doctors were overprescribing OxyContin for improper reasons, but the company failed to warn patients or stop the sale and use of its hazardous products without ensuring people were warned of the risks.

On the contrary, Purdue sales reps met hundreds of times with a doctor whose patients called him “The Candyman” for prescribing excessive doses of OxyContin described as “crazy dosing”.

What the Asbestos Industry Knew

Similarly, the asbestos companies’ own doctors and researchers were warning them that employees were getting sick and even dying from asbestos exposure, but continued to ship tons of the product worldwide without warning the public.

The asbestos industry even commissioned its own health studies that showed as early as the 1930s and 40s that asbestos causes cancer. But they hid the results of the study, and denied the extent of asbestos danger until they were driven into bankruptcy by lawsuits, not unlike the case with Purdue.

| Check out our videos about the Asbestos Industry Cover-Up of Scientific Studies Showing Asbestos Causes Cancer. |

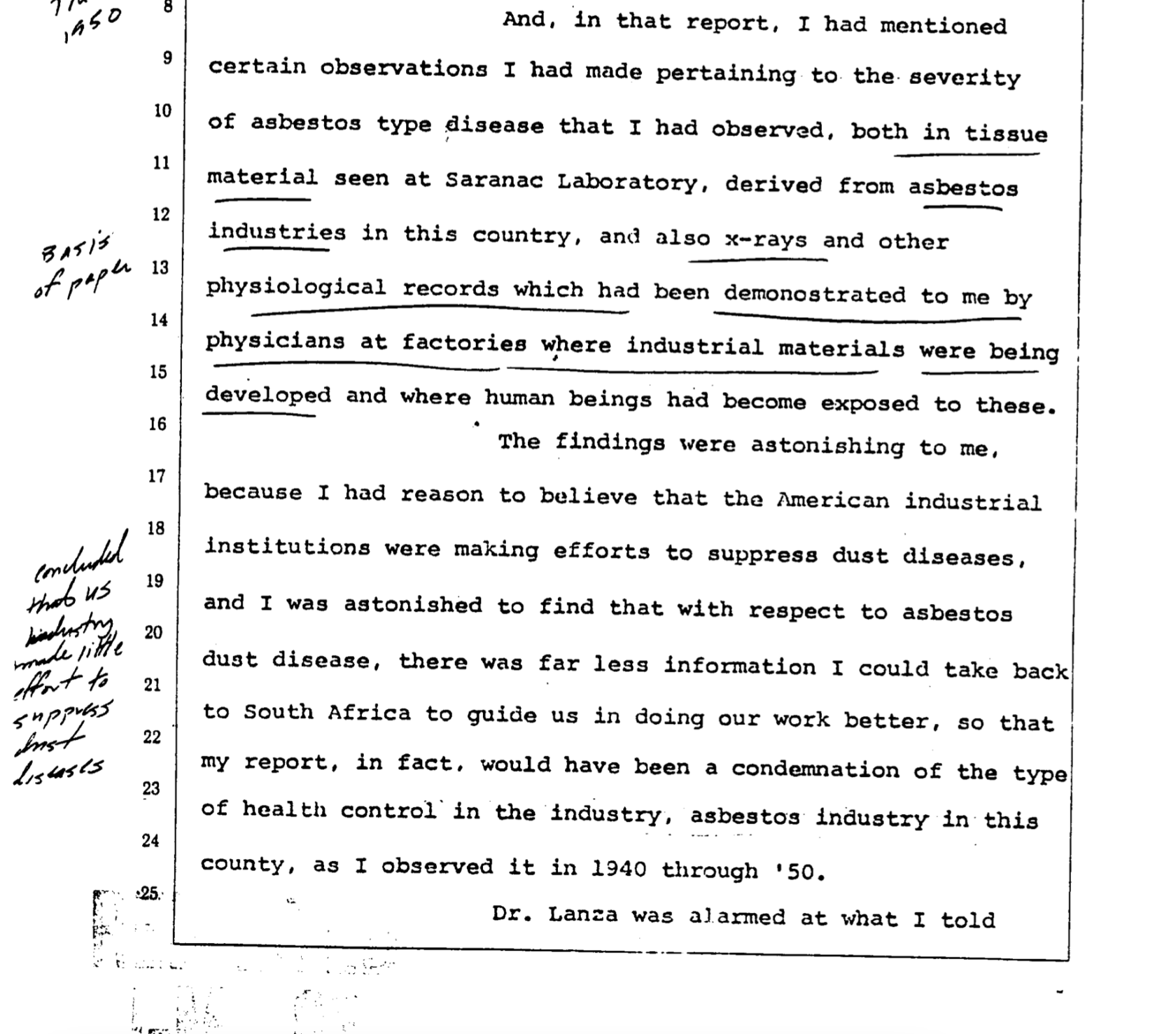

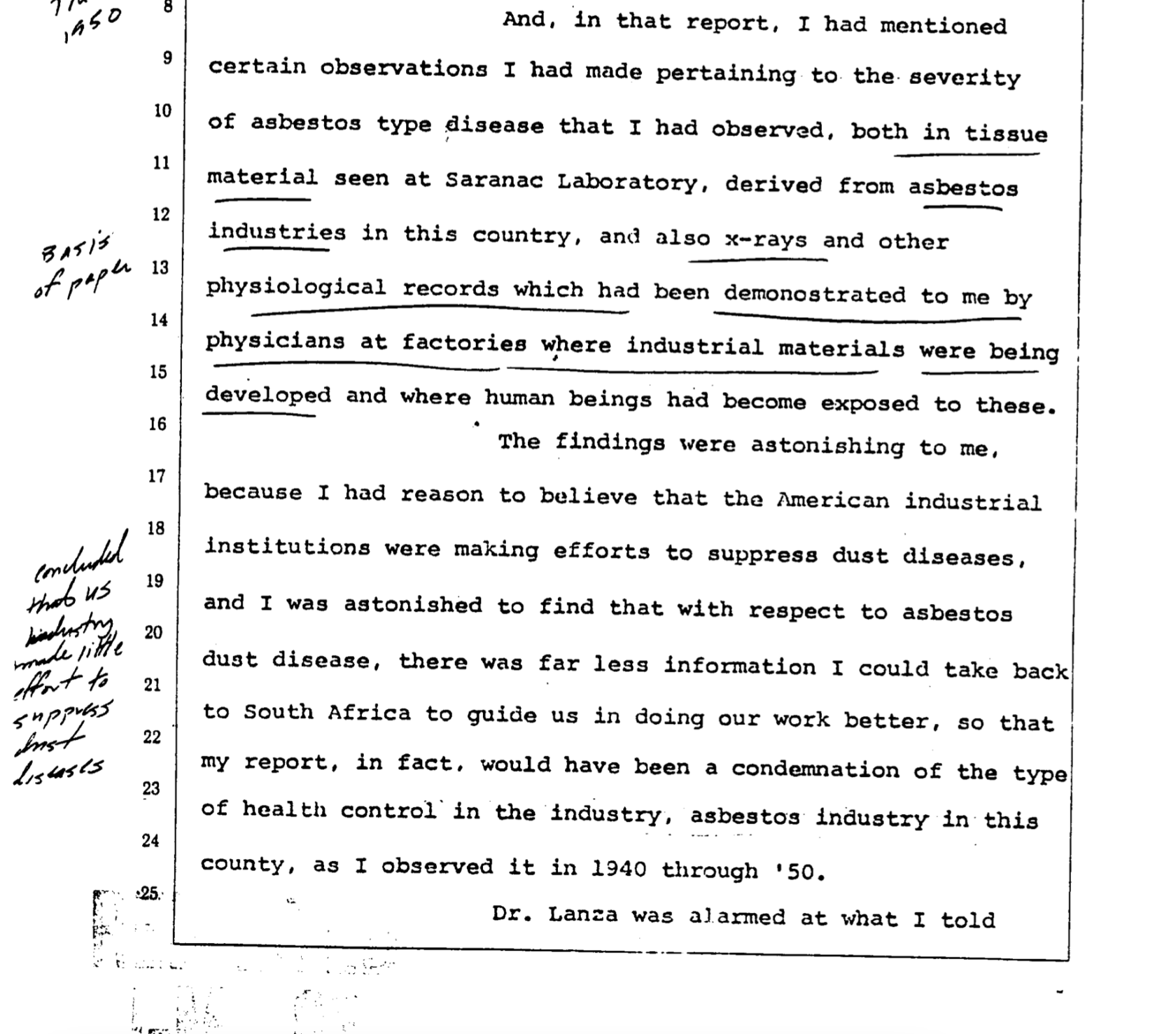

For example, at one point a South African respiratory physician named Dr. Schepers was asked by Johns-Manville (the world’s largest asbestos company) to assess the company’s health research nito asbestos, and report back what they were doing about it. (Southern Africa had many asbestos mines, and is in fact where the mesothelioma-asbestos connection was first published.

The company was hoping the doctor would say asbestos was safe, but instead he was alarmed by the extent of asbestos danger, and how little the American asbestos industry was doing about it.

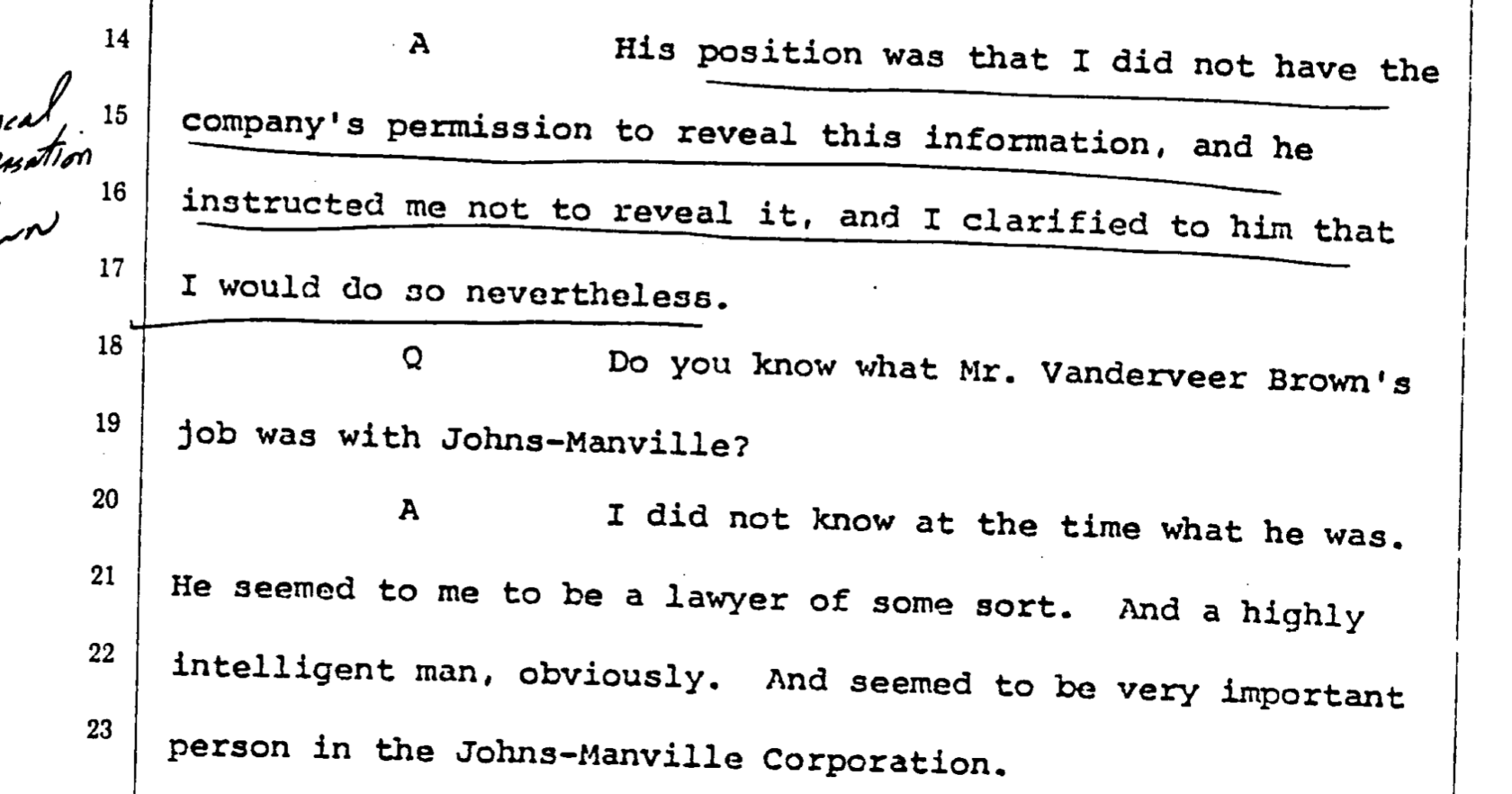

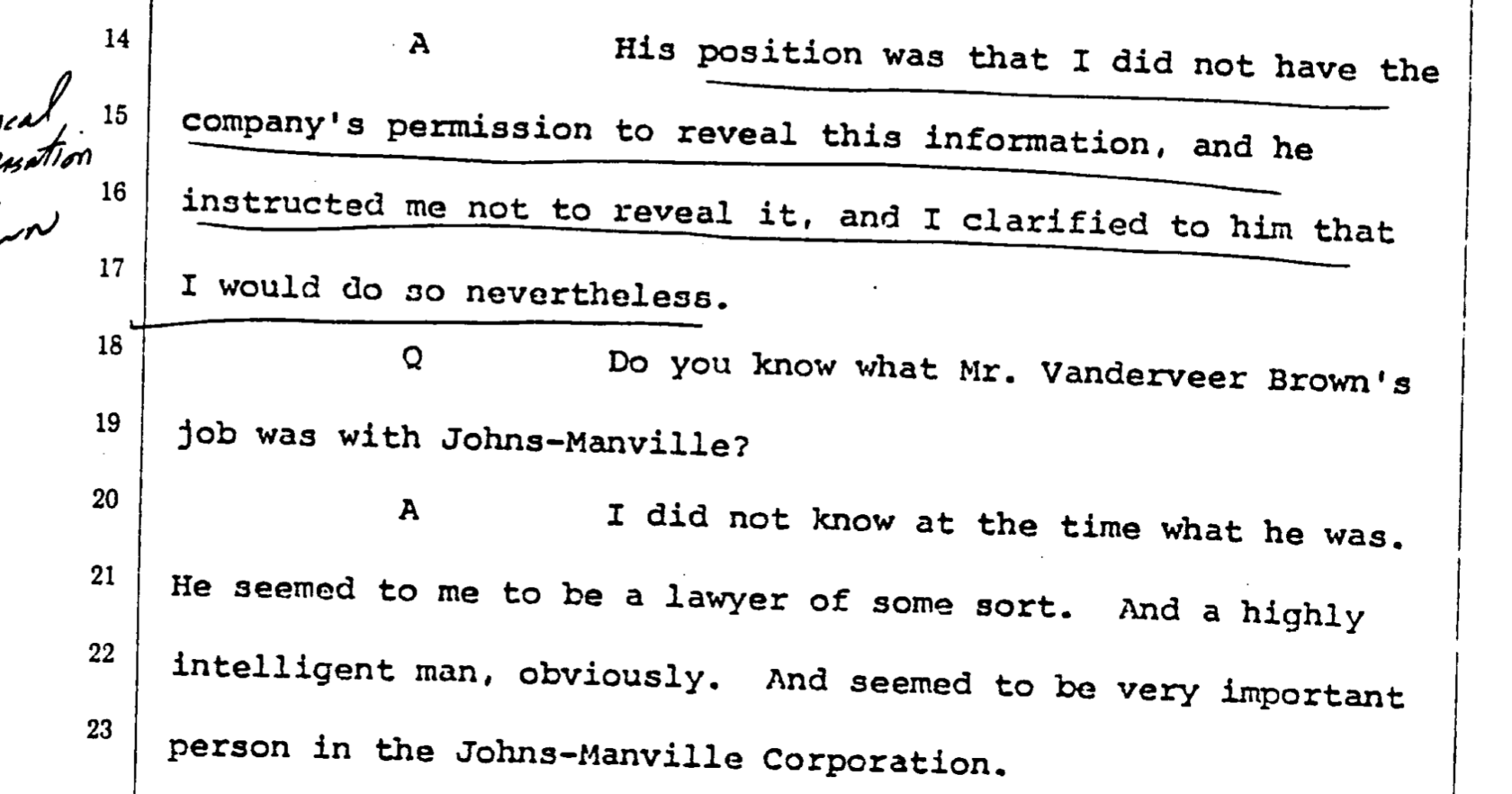

But when Dr. Schepers said he planned to publish his findings, a lawyer for the asbestos industry tried to stop him.

Companies That Declare Bankruptcy To Evade Liability

During oral arguments, the Supreme Court justices revealed a complex interplay of laws as they weighed the immunity offered to the Sacklers against the $6 billion payout. This conundrum evokes a haunting echo from history, where asbestos companies sought refuge in bankruptcy, escaping personal culpability despite evidence of willful misinformation about the dangers of their products. The parallels between these distinct crises underscore a recurring narrative of powerful entities evading accountability, shaping the trajectory of corporate responsibility.

The Asbestos Legacy:

For much of the 20th century, asbestos was heralded as a miracle material with applications ranging from construction to insulation. However, as evidence mounted about the severe health risks associated with asbestos exposure, companies manufacturing asbestos-containing products faced a moral and legal reckoning.

Executives of asbestos companies were accused of intentionally concealing the dangers of their products, suppressing scientific studies, and manipulating public perception to protect profits. Despite mounting evidence of the devastating health consequences of asbestos exposure, many companies continued their operations, exposing workers and the general public to serious health risks.

Asbestos Bankruptcy Trusts – Compensation For The Victims

Facing an avalanche of lawsuits, numerous asbestos companies sought refuge in bankruptcy, leaving behind a trail of devastated lives and communities.

As a response to the overwhelming litigation, Congress enacted reforms that allowed companies facing asbestos-related claims to establish compensation trusts during bankruptcy. These trusts were intended to ensure that people injured received at least some money for the widespread damage perpetrated by the asbestos industry.

The Sackler Family and OxyContin Lawsuits:

Fast forward to the 21st century, and a similar narrative unfolds with the Sackler family and Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin. The Sacklers, known for their philanthropic endeavors, are under intense scrutiny for their role in the opioid crisis. Accusations against Purdue Pharma include aggressive and deceptive marketing practices that downplayed the addictive nature of OxyContin, contributing to the widespread opioid epidemic.

In 2020, Purdue Pharma filed for bankruptcy, facing a deluge of lawsuits seeking accountability for the devastation caused by OxyContin. The bankruptcy filing was part of a comprehensive settlement, with Purdue Pharma proposing the creation of a public benefit company and a compensation fund to address the opioid crisis.

The Sackler family, however, sought to insulate themselves from personal liability as part of the settlement. Many plaintiffs objected to that part of the settlement, which has led them all the way to the Supreme Court.

Avoiding Personal Liability: OxyContin and Asbestos

The Sacklers’ move to shield themselves from personal liability echoes the actions of asbestos executives who escaped individual accountability despite evidence of their complicity in perpetuating a public health crisis. Both instances highlight the legal strategies employed by powerful entities to protect personal fortunes while navigating the complexities of mass litigation.

Asbestos trust agreements also largely shielded companies and their executives from personal liability. Some of the companies still exist, and no one went to jail or was personally held financially responsible for the entire asbestos cover-up. As with the mortgage crisis that led to a global financial meltdown, the buck stopped there.

The same playbook is at work with the Sackler settlement, and has landed the case under Supreme Court scrutiny.

Asbestos Trusts and the Sackler Settlement

One of the challenges in both cases is that there simply is not enough money to properly compensate for all the damage that was done. When asbestos companies were first sued, estimates were that millions of workers and consumers were injured, and millions more would only discover they were injured years later.

There is a similar problem in the Purdue Pharma case, where the lawsuits list damages far in excess of even the staggering wealth of the extended Sackler family defendants.

As one of the lead attorneys representing the plaintiffs injured by the opioid crisis stated, “whatever is available from the Sacklers, whether that’s $3 billion, $5 billion, $6 billion, or $10 billion, there are about $40 trillion in estimated claims. And as soon as one plaintiff is successful, that wipes out the recovery for every other victim.”

That’s why the money would be put in trust, with a trustee to manage it and pay out a share such that everyone with a legitimate claim can at least receive some money for their injuries, even if the amount is insufficient.

With asbestos trusts, courts first took this responsible step of preserving money for the victims, and in fact there are still billions of dollars available in asbestos trusts, and people are still able to stake their claim hoy.

Unfortunately, asbestos-related diseases and cancer can take many decades to appear, but at least there are still funds left to compensate people who are only just learning they have an asbestos-related health injury.

But the asbestos companies that established compensation trusts during bankruptcy did so with the understanding that this arrangement would shield executives from personal liability. Similarly, the Sacklers’ efforts to separate themselves from Purdue Pharma’s legal battles and the establishment of a compensation fund indicate a calculated move to protect their personal wealth.

The Health Impact on Victims: Parallels with the opioid epidemic and asbestos-disease crisis

One undeniable consequence of both the asbestos and opioid crises is the profound impact on victims and their families. Asbestos-related diseases, such as mesothelioma, continue to claim lives long after the peak of asbestos use. Similarly, the opioid epidemic has left a trail of addiction, overdose deaths, and shattered communities.

The establishment of compensation trusts, while providing a mechanism for victims to seek redress, raises questions about the adequacy of compensation and the justice served. In both cases, the settlements are often criticized for falling short of addressing the full scope of the harm caused and holding those responsible truly accountable.

Lessons Unlearned: Corporate Accountability and Public Health

The parallel narratives of asbestos companies and Purdue Pharma underscore a troubling pattern of corporate behavior. The willingness to prioritize profits over public health, coupled with a lack of individual accountability for executives, raises profound ethical questions about the responsibilities of those in positions of power.

The legal mechanisms employed to shield the Sacklers and asbestos executives from personal liability highlight a systemic issue in holding individuals accountable for corporate misconduct.

Despite evidence of willful deception and harm, the legal framework often allows powerful figures to avoid facing the consequences of their actions.

Moving Forward: Reimagining Corporate Responsibility

As society grapples with the aftermath of the opioid crisis and the ongoing consequences of asbestos exposure, there is an urgent need to reconsider how we hold corporations and their leaders accountable. The establishment of compensation trusts, while a step toward providing relief for victims, should not serve as a shield for individuals who knowingly contributed to public health crises.

Reforming legal frameworks to ensure that executives can be held personally accountable for the consequences of their actions is essential. Additionally, there is a need for greater transparency, ethical oversight, and public scrutiny to prevent the recurrence of such crises in the future.

Conclusion on the Asbestos Cover-up and Sackler Family Lawsuits

The threads connecting the Sackler family’s bankruptcy settlement and the historical actions of asbestos companies weave a narrative of corporate behavior, legal maneuvering, and the human toll of public health crises. As compensation trusts stand as a legacy of both crises, it is imperative to reflect on the lessons learned and, more importantly, those unlearned.

As the Supreme Court delves into the Purdue Pharma bankruptcy settlement, it engages in a profound reflection on the historical precedent set by the asbestos industry’s bankruptcies.

The call for corporate responsibility extends beyond financial settlements and legal structures. It demands a reexamination of the ethical foundations that guide business practices, emphasizing the importance of public health and societal well-being over profit margins. Only through a comprehensive reassessment of corporate accountability can we hope to break the cycle of crises perpetuated by willful negligence and ensure a safer, more just future.

But the skepticism voiced by some justices mirrors the ethical dilemmas surrounding compensation trusts established for asbestos victims, raising concerns about the adequacy of redress and the elusive quest for justice.

Just as the asbestos executives evaded personal liability through bankruptcy, the Sackler family’s potential immunity prompts a reassessment of the broader landscape of corporate responsibility. The Supreme Court’s forthcoming decision may offer not just a resolution to the Purdue Pharma case but a pivotal juncture for redefining how corporate executives navigate legal accountability in the aftermath of public health crises.